How to Build Resilience and Clarity

On this episode of the Social Chameleon Show, we have our guest Mitch Weisburgh, an educator and expert in the art of MindShifting. Mitch has spent over 40 years helping people and organizations unlock their true potential, from founding one of America’s earliest computer learning centers to driving nonprofit innovation and building communities for lifelong learners.

Mitch brings practical strategies from his book, “MindShifting: Stop Your Brain from Sabotaging Your Happiness and Success,” showing how our minds get stuck in survival mode, and what it really takes to get unstuck. In this conversation, you’ll hear real-life examples, honest reflections, and plenty of actionable techniques to break free from limiting habits, handle change, and build the resilience needed in work and life.

Whether you’re an educator, leader, parent, or just someone feeling overwhelmed, you'll find relatable stories and simple tools you can start using today. Tyson and Mitch dig deep into how we respond to stress, why groupthink traps us, and how self-awareness and curiosity can lead to more fulfilling decisions. You’ll also learn how top performers reset after mistakes, why “being sure” can be a warning sign, and how AI is changing the way we learn and adapt.

This episode isn't just theory, it's down-to-earth advice for anyone ready to reshape their thinking and step forward with confidence.

Enjoy the episode!

Key Themes

- Mind shifting and self-awareness

- Managing fight-or-flight reactions

- Building resilience through curiosity

- The power of positive self-talk

- Handling groupthink and social pressure

- Effective collaboration and conflict resolution

- Using practical techniques for personal growth

Lessons Learned

- Survival Mode Awareness

Learn to spot when your brain reacts out of survival, so you don’t get stuck in fear, stress, or anxiety. - Getting Resourceful Fast

Shift from survival to resourceful mind using breathing, self-talk, or quick distractions to think clearly and act wisely. - Breaking Groupthink

Understand how group pressure shapes your decisions. Build self-awareness so you don’t just follow the crowd. - Handling Conflict Effectively

Discover five conflict styles, and use resourceful communication instead of fight-or-flight reactions to build better relationships. - Building Everyday Resilience

Accept that most problems don’t have one right answer. Stay adaptable by testing solutions and learning from feedback. - Mindful Self-Talk

Replace harsh or negative inner dialogue with open, curious questions that unblock your thinking and encourage growth. - Curiosity Over Certainty

Notice when you feel totally sure about something. Use curiosity to explore new perspectives and avoid stuck thinking. - Motivational Interviewing Basics

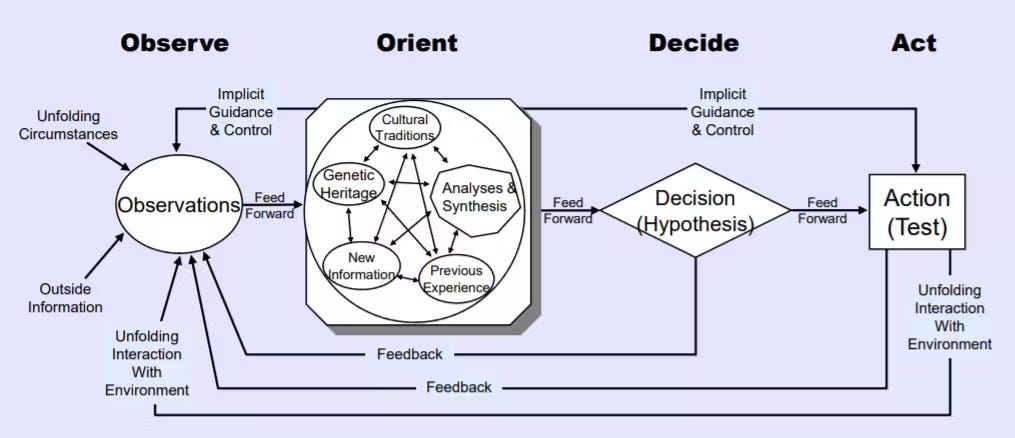

Help others change by asking gentle, open questions. Let them discover their own reasons and solutions, instead of arguing. - OODA Loop Thinking

Use the observe, orient, decide, and act strategy to solve problems step-by-step and keep improving after setbacks. - Collaboration Skills

Choose long-term collaboration over short-term competition or avoidance. Listen, share goals, and create win-win results.

MindShifting: Stop Your Brain from Sabotaging Your Happiness and Success.

🧠 Rewire the Loops Holding You Back

In MindShifting, educator and entrepreneur Mitch Weisburgh shows how much of our struggle comes from mental autopilot—fear, blame, avoidance—that keeps us stuck. The book explains why our brains default to these patterns and offers more than 50 techniques to shift into mindsets of Resourcefulness, Resilience, and Collaboration.

It’s not theory for theory’s sake. Weisburgh gives practical exercises you can use in the moment to catch self-sabotaging thoughts, reframe problems into opportunities, and respond with clarity instead of reflex. For leaders, educators, and anyone serious about growth, MindShifting is a manual for reclaiming your brain and directing it toward progress.

From 1981 through 2000, Mitch founded and ran Personal Computer Learning Centers of America, training adults in the use of computers, growing the company to over 130 employees.

Mitch Weisburgh cofounded Academic Business Advisors in 2005, which helped organizations make a difference and reach more students in US schools. He has started various nonprofit organizations in education such as Games4Ed and Edchat Interactive.

Mitch’s book, MindShifting: Stop Your Brain from Sabotaging Your Happiness and Success came out in December, 2024, and focuses on techniques to change from mindsets that hold us back to ones that propel us forward. Since 2018, Mitch has been creating content and teaching MindShifting and Sensemaking and has started a Mindshifting Community for educators.

Career:

- Founded Personal Computer Learning Centers of America (1981–2000). Trained adults in computer use. Scaled to 130+ employees.

- Cofounded Academic Business Advisors (2005). Helped organizations improve education and reach more U.S. students.

- Founded nonprofits like Games4Ed and Edchat Interactive.

Current Work:

- Author of MindShifting: Stop Your Brain from Sabotaging Your Happiness and Success (Dec 2024).

- Creates content and teaches MindShifting and Sensemaking (since 2018).

- Leads MindShifting Community for Educators.

- Writes the MindShifting with Mitch newsletter.

Weekly Challenge Trophy Weekly Challenge

Think of something you are absolutely sure about. It could be something you believe you can or can’t do, or something you’re convinced someone else is wrong about. Then, challenge yourself to get curious about it. Ask yourself: “What if I’m not completely right?” or “What else could be true here?” See if you can open up your thinking, even just by 10%, to other possibilities or perspectives.

The idea is to notice those moments when your mind is locked in certainty, and instead of digging your heels in, practice being just a bit more open and curious. This small shift can lead to big changes in how you relate to challenges, other people, and your own self-talk.

So, pick one thing you’re sure about this week—and get curious!

SELECTED LINKS FROM THE EPISODE

Resources Mentioned

Here’s a detailed rundown from the episode:

Conflict and Collaboration (Dec 2025) by Mitch Weisburgh

This is Mitch’s upcoming book, which he refers to several times, especially when discussing motivational interviewing and groupthink. He describes some of the key concepts that will appear in this book, like handling conflict and collaborating effectively.

Recommendation: Discussed as a future resource with specific frameworks.

Meditation Apps

Never Split the Difference by Chris Voss

I mention this as a favorite on negotiation, related to the discussion on conflict and collaboration. I describe it in the episode as a book that reframes how you think about these things.

This is recommended by Chris Voss in the above book, and is an excellent guide to saying and using the word “no,” which a lot of us have a hard time with.

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

I reference Kahneman as someone who, “even though he knows all these things, he’s still fooled by a lot of these things.” It comes up during a discussion of cognitive bias and how being an expert doesn’t make you immune.

Recommendation: Offered as an authoritative source on the science of thinking and cognitive bias.

The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene

- Law cited: “Never Outshine the Master”

Mitch and I use it to discuss group dynamics, leadership, and power plays related to groupthink and reactions to conflict within groups.

Wherever You Go, There You Are by Jon Kabat-Zinn

I mention rereading it and connecting a story about irritation with habits to the book's themes. He references how the message helped him reframe a daily annoyance and let go of being upset.

Recommendation: Suggested as a resource for mindful acceptance and reframing daily experiences.

Stoicism (Epictetus/Stoic philosophy references)

I share a personal story based on a teaching from Epictetus about voluntary discomfort and preparing for adversity. He applies this to his own family practices, like eating simply once a month.

Recommendation: Used as a practical philosophical framework.

Bill Walsh: The Score Takes Care of Itself

& Phil Jackson: Eleven RingsMitch notes these as visible in Tyson’s recording background. He connects the philosophies of these coaches to the episode’s themes about resilience, mind shifting, and emotional regulation.

Detailed OODA Loop

More Interviews With Outstanding Guest's

Episode Transcripts

Show notes and transcripts powered with the help of Castmagic. Episode Transcriptions Unedited, Auto-Generated.

Tyson Gaylord [00:00:05]:

Welcome to the social community show, where our mission is to help you learn, grow, and transform on your path to becoming legendary. Today, we're diving deep with someone who's cracked the code on why smart, capable people get stuck in their own heads. Mitch Weisberg has spent over four decades shaping the way people learn and adapt in a changing world. From founding one of the earliest computer learning centers in America to advising education leaders and launching nonprofit initiatives like Games for Ed, Mitch has dedicated his career to helping people unlock their potential. Most recently, Mitch has been teaching the art of mind shifting and sharing practical ways to build resilience and capability clarity through sense making. His book, stop your brain from sabotaging your happiness success offers tools to break free from limiting mindsets and step into forward momentum. Mitch doesn't just talk about learning. He creates communities of practice for educators and lifelong learners alike.

Tyson Gaylord [00:00:57]:

Whether you're navigating change, designing your next chapter, or seeking ways to overcome mental roadblocks, this conversation will give you tools to reshape your thinking and your life. Mitch, welcome to the Social Chameleon show.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:01:11]:

Tyson, thank you for having me on the show.

Tyson Gaylord [00:01:13]:

Absolutely. I mean, it's hard to pass up your pitch. You're talking about mind shifting, and you had a bunch of things in there. I was like, well, I've got to have this guy on. So you do have your book, your first book, Mind shifting Stop your brain from sabotaging your happiness and success. If you guys want to get the book, I'll link in the show notes. You guys can go get that and read that on your own. But what is one story you'd like to highlight from your book?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:01:37]:

So one of the stories actually comes from somebody who was taking the course, which, you know, the book was modeled on a course that I teach. And this is a woman who, you know, she and a friend had a. Have a third friend who was in an abusive relationship, and they were going over on a Saturday to help her move into a safe place. Okay. Okay. And they had given her a list of things that she had to do to prepare, and then they were going to go over Saturday, and they're just going to move her and her kids to a. To a. To a safe place.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:02:18]:

They show up Saturday morning, and their friend had done nothing on that list.

Tyson Gaylord [00:02:24]:

No.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:02:25]:

And so you can imagine it's like, we're giving up our Saturday mornings, you know, and what. You know, we just gave you a simple list, and you didn't do any of them. And it's like, that's what's going on in their heads. Okay. But the woman was taking the mind shifting course, you know, and so, so she says, well, wait a minute, you know something, let me, I know that I'm in survival mode right now. I'm just reacting to the situation. Let me calm myself down. And so she and that second friend did some breathing exercises to calm their minds down.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:02:56]:

And then once they were more in control over their own brains, they were like, you know something? What's really important to us and what was really important to them is that they had a friend who needed help to move into a safe place and they were going to help her set up with a better life. And once they were in control of their self, it's like they understood like, you know, this poor woman, you know, she's, she's taking care of her kids, she's taking care of the house, she's trying to avoid being beaten. She's, she's, you know, she's reacting to so many different situations. This list of things to do was kind of a nice to have, you know, but, but she, she had to survive first. And so the fact that she didn't do the things, it was just like, there's no way. But, but what they did is they, they, you know, they were able to regroup because they got control over their minds and work with her, get all these things done that could have been that, you know, they thought were going to be done earlier. They spent the Saturday they moved her to, to, to another place and they were all like, wow, you know something, look what we did today. And so that's the power of just understanding how our brains react to situations, how we can control them.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:04:06]:

If we don't control them, then we're just reacting and you know, anger or fear or anxiety or whatever. But we can learn to recog that. We can calm that part down. We can access our resourceful minds. And when we do, not only are we a lot more effective, but we're a lot happier and we feel more fulfilled.

Tyson Gaylord [00:04:27]:

So would that be getting into the parasympathetic state?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:04:32]:

Yes. So. Right, yes. I don't really actually, you know, those. I tried to write the book and I tried to teach the courses as much as possible without using terms that, you know, like sympathetic or parasympathetic. But you, you know, you hit it. Exactly. That's your, you know, your calm.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:04:53]:

You could call it equilibrium, equanimity. I call it the resourceful mind or the sage mind. You can say it's, you know, the prefrontal Cortex, but those are all related.

Tyson Gaylord [00:05:03]:

And so I guess, please, please correct me however I get this wrong or mixed up. So I understand that system is if, if you're in a heightened state, you can't think properly.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:05:15]:

Right.

Tyson Gaylord [00:05:15]:

You're in like the survival mode versus, you know, I'm sorry, if you're out of that state. But when you get into that state is when you, you're able to kind of like turn that kind of offline a little bit and then you're able to start thinking again. Is that how we're kind of thinking about this?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:05:27]:

Yeah. So I'm gonna, I'm gonna just riff on that for a minute and just kind of back up and say, and this is obviously oversimplified. Okay, sure. Because the brain, you know, it's, it's, the brain is probably the most complex system in the universe. I mean it's got, you know, hundreds of billions of connections between neurons and, or, you know, so, so to say it's got, you know, I say this got two parts is, you know. No, it's got hundreds of parts. But, but if you, if you think about it as having your survival parts of the brain which, which started evolving with the earliest multi celled organisms that could move. And those organisms, you know, over, you know, very early on in evolution, they learned how to rapidly assess if they were in danger and take some type of action.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:06:27]:

And so, and then it, you know, it, it developed and you know, it could be moving, it could be fighting, it could be blending in with the environment. But it's like this is a danger. This is what we have to do. Focus the entire organism on that type of situation. And then you had to be able, you had to be able to do that quickly so that parts of the brain wake up in like 2 to 3/100 of a second from some stimulus.

Tyson Gaylord [00:06:57]:

It's not even a blink.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:06:58]:

It's not even a blink. Okay. And they have to be able to come to decisions on, on not full information, you know, just, you know, quickly like this is a danger because otherwise if they're wrong, the organism isn't going to survive. And then, and then, and then focus you and then, you know, like how you forgetting whether it was like a billion years or a million years, but you know, but hundred, you know, hundreds of millions of years later with the vertebrates and the mammals, we started developing a higher order system of thought, the, you know, our cortex and, and, and that's the part of the brain that was more developed in mammals and more developed in the great apes. And really it's pin human race is really the pinnacle of that. And that's where we get our ability to think critically, to think creatively, executive function, to really connect. But that part of the brain wakes up in two to three seconds. So if you think about it, something happens within two to three one hundredths of a second.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:08:11]:

Our survival brains wake up more often than not. They're assessing it as a danger because that's what they're primed to do. They come up with a thing to do. And then when our prefrontal cortex or, you know, survive or our resourceful brain wakes up, they're saying, okay, this is what we're going to do in. Give me a justification. And so almost always what we think of reality is just this justification for what we've emotionally determined to do. Because our survival brains thought we were in danger. And so in the way they can they prevent the resourceful parts of the brain from, from activating is through stress hormones.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:08:51]:

So the stress hormones, I mean, they give us, you know, superhuman strength, they allow us to focus our efforts, but they also inhibit us from being able to take in new information to be able to. We can't think critically, we can't think creatively. You know, we can't really have an open discussion with other people. We can't explore. We can't relate things to what we most value. It's like we're just focused on this is what I have to do. So, so what, you know what mind shifting is the first part of mind shifting, the resourceful part of it is about is how do you recognize when you're in this limbic or this survival mode? And then how do you quiet it so that those stress hormones start coming down? And then how do you access your resourceful parts of the brain and stay in resourceful mode even when things start to go wrong again?

Tyson Gaylord [00:09:48]:

So that's part of your, your three core capacities that you, you have on your. And your. Was on your, on your thing, the resourcefulness, the resilience and the collaboration. So I, the, I guess the, the only way maybe I, off top of my head I can think of is getting into that state. Is, is a breath like you were saying in that story. Is there, is there more ways or is that the best way or the easiest way? How do you think about that?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:10:12]:

Well, so again, this is probably a simplification, but I use that. There's three ways of getting into that state. Okay. And then a fourth way that I'll go into afterwards. But the Three ways is first, is first of all self awareness. Sometimes just realizing that you're in a survival state of mind or you're, it's like, oh my gosh, I'm acting in a survival mind. Again, this is my limbic brain. And that, and that's enough.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:10:38]:

Okay, Sometimes we can just talk to ourselves like, well, what do I really want to happen here? Or you know, I know I can't do this, but if I could, what might I do first? Okay, so there's positive self talk, not argumentative self talk. Not like, you know, no, stupid, you just got to work harder, you know. No, it's, it's, it's, it's talk that kind of, that opens you up rather than furthers the release of the stress hormones. And then the third way is some type of distraction. And so meditation and mindfulness are two, are two methods that are very effective. Taking a walk, taking a walk in nature, if, you know, doing some sports or athletics, if you're into music, listening or playing music, if you're into art, looking at some art, doing some art, you know, so it's something that takes your mind off of or away from your, your, your living survival mate. So that, so that it's naturally going to start calming down and then using your positive self talk to kind of direct yourself to your, you know, your resourceful mind. So those are the three things that you can do yourself.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:11:51]:

Self awareness. Sometimes that's enough self, self talk. Sometimes that's enough with, that's not enough meditation or distraction. And that could be as little as like 30 seconds or a minute very often. And then, you know, there are times for all of us that we can't do that ourselves. You know, like, we're just like really angry or we're really anxious and, and so I, I, I don't know what to do. And so in those times, it really helps to have other people that you can go to. So for some, for some of us it's, it's our spouse or the person we're having a relationship with.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:12:28]:

My kids are adults I can call my kids, you know, and, and, and it's funny because when I call them, they're like, dad, you wrote the book. You know, like, you know, I'll just, I'll just give you one of the techniques in the book and, but that's all I need. You know, I just thought I couldn't do it myself. I needed a third party to just walk, walk me through that.

Tyson Gaylord [00:12:49]:

Yeah. So this is kind of how I'm here. I'M hearing that whole thing. So when you're in this like fight or flight mode, then you take these kind of, I don't want to say distractions, but something that gets your mind out of that. You do one of these things and then you can go off to that side, you know, do your art, do your meditation, whatever it is, what technique you've chosen, or it works with you breathing and then breathing, whatever it is. And then you can go, when you're over on that other place that's just metaphorically. Then you can start to kind of calm down and say, okay, now I can think. Okay, what happened? What do I need to do?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:13:20]:

How do I respond?

Tyson Gaylord [00:13:21]:

How do I react? How do I, how do I come up with 500 bucks because my car broke down? How do I, how do I do whatever it is? Right? Is that, is that correct? Am I summarizing that correctly?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:13:29]:

And it's, it's funny because, you know, like I'm, you know, they're, they're built into mind shifting, but a lot of us do that anyhow. I know growing up, you know, my mom was always, before you say something in anger, take a deep breath and count to five. And I never, you know, when at, at six years old, seven years old, I'm not thinking about, oh, that's mind shifting or anything, right? Hey, you know, it's like, wow, you know something? She never studied my, but she just knew that. And that's, you know, that really helped.

Tyson Gaylord [00:13:59]:

I do notice for myself, you know, when I, I, I heard a meditation a lot and I was like, it's not for me. And I, I can't do that. Of course, all the cliches, right? And then I said, and then I came across Sam Harrison. He had an app. And I was like, wow, let me try this. And then it was nice little nuggets, you know, of, of information. We, I think it was like a 30 day thing and just at the base level, just learning how to catch myself in a thought, I noticed just that thing right there. It helps a lot with, you know, like, you know, you're on your phone, you're scrolling through whatever it is or something like that.

Tyson Gaylord [00:14:39]:

I, I was, I started to notice, like, oh, wow, I can catch myself in this thought now. When I would get angry, I could catch myself in that thought or I really want to say something that was going to cut deep and I got to come back for you. Before this, I would probably have just said the thing and just flown off the handle and, you know, whatever. But after I learned that technique. I was able to kind of, sort of in the moment kind of look, okay, I must say, look down on myself in a way and say, oh, okay, hold on here, buddy. You're. You're upset.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:15:05]:

You're.

Tyson Gaylord [00:15:05]:

You're kind of getting a little heated.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:15:07]:

You.

Tyson Gaylord [00:15:07]:

You want to win the argument or prove your point or whatever it was I was trying to do or whatever. But after learning that, even I haven't done it in a long time, since I first did it. I think I did it for like a year straight. And then. But since then, I still have those skills.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:15:20]:

Yeah.

Tyson Gaylord [00:15:20]:

And it feels like you just. I personally, I just kind of need a tune of. Every once in a while, I'll notice myself not noticing, which is interesting in and of itself. But, yeah, I. I have to have experience with that. And it's interesting, once you learn that, how you can kind of look upon yourself and say, okay, well, hold on here, buddy.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:15:36]:

You're.

Tyson Gaylord [00:15:36]:

You're in a bad state right now. Let's. Let's, you know, readjust.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:15:39]:

Let's shift and, you know. So I'm gathering you're a sports fan, because I see the 49ers, okay? But you look at an elite athlete in any sport, and look what, what. Look what they do when something either goes right or. Or especially when. When something goes wrong, it's like they know how to. It's just like, it's gone. It's like, okay, I let this, you know, football, you know, I. I threw.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:16:03]:

When he cackled the quarterback. It's like, you know, you don't. They don't beat them, continue to beat themselves. It's like, okay, that's done. What am I going to do the next play? And so they learn those techniques on how to very quickly switch from what they naturally would be. Was dwelling on it like, oh, I'm a horrible player. Look what I just did. And it's.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:16:21]:

If you're thinking that, like, that the next play, you're gonna do something stupid again, okay? But when you're. When you can reset and prepare, like, you're just ready for the next thing, it's like, I'll, you know, maybe after the game is gone, I'm gonna watch the film and figure out what I. What I did wrong. You know, whether it's in tennis or. Or soccer or football or, you know, whatever the. The sport is. But while I'm in the game, I'm gonna do a quick reset, and I. And I have to be in resourceful mode because I have to Be at my peak.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:16:53]:

Yeah.

Tyson Gaylord [00:16:53]:

And it's interesting if we continue the sports analogy, I can feel like I notice when a guy does get in his head and you see him, he's a little timid. I made a guy, you know, start dropping balls or the quarterbacks, like, you know, he throws a pick in the next play, you're like, oh, you're just throwing checkdowns. You're just throwing, you're just handing the ball off a lot. And you see a guy getting his head. And when it's the other team, I really love it. I'm like, hey, look, this guy's in his head now. Hey, let's go, let's, let's, let's, let's pounce on this guy. He can't control himself.

Tyson Gaylord [00:17:18]:

But I also, you know, like these interviews, I'll go back and I'll watch them and I'll critique myself. Like, oh, I should have, I should have been quiet there. I should have said this or maybe I should have done this or maybe I should have told that joker. But I, you know, over 100 and something episodes now, you know, I, you know, I've got, I, I, you know, so even with, you know, in your professional life, you know, you, you record these zoom meetings, whatever, go back and watch yourself and give yourself honest critiques and you know, don't over overly critical, but also be honest with yourself as well.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:17:45]:

And, and then having somebody that you can go to also like you, you work with, with, you know, entrepreneurs or solopreneurs entrepreneurs, and you know, they'll probably come to you and they'll just be like, oh, geez, nothing's going right. And, and you can't give them advice at that point because the first, until they're in a resourceful point of mindset, they're not ready to receive anything. So your first job is to, is to get them right. Isn't that in your coaching, isn't that what you do?

Tyson Gaylord [00:18:16]:

Absolutely.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:18:17]:

Yeah.

Tyson Gaylord [00:18:17]:

You, sometimes you just got to listen and let them get that all out. And a lot of times what my experience, what I found is, is as they're talking, they're kind of figuring it out themselves, right? Or just a little, a little, a little probe here, a probe there. And it's like you've just answered the whole question for yourself. And it's like, well, there you go. It's like, oh, thank you so much. This was a great conversation. I was like, I said nothing.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:18:37]:

No, because most of us, and so this is, you know, in the, in, in this book that's, that's coming out the Conflict and Collaboration book. One of the key techniques that we go over is something called motivational interviewing, which comes from social work, which is. Which is all about getting the other person to understand where they're ambivalent about something and kind of sort through for themselves what's really most important to, to them and what they should do next. And once they start doing that, the solutions start coming to them. But they couldn't do it without somebody walking them through the questions to get them to, to ask themselves the same questions, the right questions, or to. Or to think about the questions in a different way.

Tyson Gaylord [00:19:25]:

I love that because I think there's a power in living that examined life. I talk about this quite a bit on the show and. But that's to me, in general, I think that's missing from a lot of society especially. I know I think I can only speak for America, but I kind of feel like I see that in the Western world a lot where we don't examine things, we just kind of go through things. But the power of sitting down and examining what do you want? What are you doing?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:19:48]:

What are you doing right?

Tyson Gaylord [00:19:48]:

What are you doing wrong? Where do you want to be? Are you on track? All these things. Asking those questions will give you direction. We'll give you a leg up over, I think 95 at least of all people.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:19:58]:

Right? Right. And I think, you know, a lot of that comes from again, our limbic minds, okay. The. Which when everything is binary, something's good or it's bad, period. Okay? And just another aspect, you know, we've gone into, you know, being angry and fight or flight or, or even freeze as, as the, you know, as prime reactions from our survival brain. We should also be conscious that there's two more types of actions that are. Our limbic brain, our lizard brain uses also is looking to conserve energy, of course. So in conserving energy, it wants to do something.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:20:41]:

It wants the organism, you to do something where you don't really have to think about it. So it's actually looking to. Looking to come up with something that you already know how to do. Well, what are your habits? What are your fluencies? Okay. And so it doesn't have to think anymore if you know, anything. Anytime this happens, this is how I react. Okay. And you know, kind of rules, roles are like that.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:21:02]:

And then the fifth type of reaction is as human beings, we have this is incredible drive to be part of groups. And that's, you know, that's what's one of the things that's made us like the, you know, the alpha animal on the planet, right? Because we can build cities, we can build technology. Look at all the things that we, we can do in groups. We, we have family groups, we have work groups, we have religious groups, we have social groups. You know, we have this, this strong drive to be a member of a group and to blend in and do whatever the, the rest of the group is, is, is doing. But the flip side of that is that when we're doing that, we're not thinking. And so we have this thing that like, oh, you know, everybody in my group is doing this and you know, like that becomes a, that's, that's the thing to do. We don't even, we don't evaluate it.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:22:01]:

Then when that gets challenged like you're wrong or why are you doing this? Or here's another way, then our limbic brain comes in and says, oh, this person is challenging me. That's bad. I have to react and I have to fight or flight. You know, I have to fight them or I have to run away from this. Avoid it. And so then you get the fight or flight and you get the, you know, those, those fear hormones that are flooding your brain and preventing you from critically thinking and being creative and being empathetic and, and linking to your higher level values. So, so when we're doing things and we think that these are the things, these are things that we have thought out, but there are things that have been, that have been determined by our survival brains that then have, have. When our resourceful brains, when our prefrontal cortex is finally woken up, our survival brain is basically saying, give me a justification for this.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:23:04]:

And so, you know, it's like, well, you're doing this because it's the best thing to do. You're doing this because it's logical. You're doing this. Everybody else is doing this, so this must be the right thing to do. And so that's our reason. But the reason actually came after we had already made the decision to do do it, right?

Tyson Gaylord [00:23:18]:

Our brains come up with the reason after we've already made them usually emotional decision, right?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:23:22]:

And, and functional MRIs have confirmed that, you know, they've confirmed that first, you know, that those parts of the brain that come up with a thing to do and rule it, that we're going to do it. Those parts of the brains are firing first and then after they've already calmed down, that's when the, the thinking part of the brain fires up. So it's naturally it's just like, okay, this is what we're doing. This must be why.

Tyson Gaylord [00:23:45]:

So that phenomena you're speaking about. I try, I might have the terminology wrong. Please correct me. So, like the group think kind of mentality. Yep. I try my best to not belong to a group. It in, in the best I can. I know it's, it's not entirely, you know, you know, practical, but, you know, whether it's, you know, politically or Religiously, except the 49ers, I'm part of that group and I'm gonna stay there.

Tyson Gaylord [00:24:11]:

But of course, but I, I. Because I don't want to fall for this group dynamic, this group think. Because you do kind of start to like, like we're talking about here. You do try to start to justify, like, well, my group does this thing good or bad. I'm not, I'm not saying any which way here. And so then maybe you don't agree with it or you're, you, you're raised a different way or something like that. And then you start to kind of justify like, oh, my group's doing this. So I think it's okay.

Tyson Gaylord [00:24:38]:

And then what can happen sometimes is that just, you know, extrapolates out to greater and greater things, typically on the negative side. So I like to try not to do that. Where is my thinking wrong? And maybe is there, or is there maybe something to that where we can try to avoid some of that?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:24:57]:

How.

Tyson Gaylord [00:24:58]:

I know I'm kind of rambling a little bit here, but I'm trying to kind of put my head around this thought. If you, if you kind of get what I'm saying. I don't know if we can.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:25:04]:

Well, I think what you just noted, you, what you've just shown is that you have this tremendous self awareness that there's a group and you're not just going to do something because of the group. That self awareness has been something that you've learned how to do. Most of us never really learn that. So most of us, when we're part of a group and the group does something that's a little bit off from what we want to do, it's like, well, you know, something everybody else is doing and I'll do it and then that becomes the new center and then there's the next thing you. Could you, I think one, you know, one story is, you know, you're at, you're at Thanksgiving, which is around the corner, right. So you're at Thanksgiving and the turkey comes and it's way, way overcooked. It's like, dry as toast. Okay.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:25:57]:

And the host at host said, you know, how do you like the turkey? Okay? And it's like, yeah, it's. Well, it's good, you know. And then the next person says, yeah, this is tasty. And so, like, you know, then you're asked like, three days later, how was the turkey? And it was like, oh, yeah, yeah, it was. It was good. Because, you know, there's that conditioning. You've heard it five, six, ten times about how good the turkey was. That.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:26:19]:

That. That just changed in your brain. There's. There's another story. Like, have you. Like, I think it's called the. The Abilene story because it. It took place in.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:26:32]:

In Texas where, you know, a bunch of people, you know, say three people are discussing, like, you know, what are we going to do for dinner? And somebody says, well, there's this restaurant about an hour and a half away, or there's this restaurant. And then somebody looks it up and says, oh, it's only an hour and a half away. And somebody says, yeah, it would take me, you know, two minutes to get changed, and then we can go. Okay. Now, if you evaluate that conversation, nobody ever said they wanted to go to that restaurant.

Tyson Gaylord [00:27:02]:

I didn't even realize that.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:27:04]:

Right.

Tyson Gaylord [00:27:04]:

I was stuck on an hour and a half away. That's too far.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:27:07]:

Right? Okay, okay. But it's, you know, it's special. Whatever, you know, 45 minutes away. Okay. But like, you know, but you just feel like this part of the. Somebody says, it's only, you know, an hour and a half. It's only 45 minutes away. You know, somebody suggested the restaurant.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:27:24]:

Well, then in your mind, it's like this. If there's. If they're naming their restaurant, they may want to go, so, oh, it's only 45 minutes away. And the next person says, well, I can just get ready in 15 minutes. Well, you know, nobody said that they wanted to go. And you go, the. Maybe the food wasn't so good. Maybe you didn't want to go there.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:27:39]:

But on the way back, you know, you're having this conversation like, well, that was fun, right? Yeah. We should do this again sometime. Well, how about in three weeks? Yeah, let's. Let's. Let's go back in three weeks. And you just kind of get locked into this thing that, you know, the group is doing. But what, what you're saying is, you know, you do, and you probably, you know, you. You probably help your clients do.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:27:58]:

It's like, well, wait a minute. Are you doing this? You know, if you can step back a minute and just ask yourself, what do you really want to do? Okay. And so it begins with a self awareness. And then. And then, you know, maybe the self talk, like, you know, what, what. What do you really want to do? Or maybe it actually takes a while to distract yourself. Like, okay, you really caught up in this. Why don't we take a walk for, you know, and just talk about nature or something, you know, football for a couple minutes.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:28:30]:

Okay, now, like, now, now that, you know, let's just think about this. Like, in this situation, what, what do you really want to do?

Tyson Gaylord [00:28:37]:

Yeah. I encourage my children especially to, you know, politely challenge these things that they feel are a little off or maybe goes against something that they're thinking. And what, what I, what we do typically find, in my experience, and also I hear this from my kids as well, is, is when you do challenges, group dynamics, there's something. And I'm trying to work out what this is, and I think you can help me with this. Is, is this. When you challenge this, this dynamic or this consensus, whatever, is this an ego thing, is an identity thing? Like, what's happening where people have this visceral reaction to you not going along with it or you're not listening to them or what is that?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:29:18]:

So we have, I mean, it's obviously complex, but again, we have this drive to belong to groups, and we also have this tremendous fear of being rejected by groups. And fmris on the brain have shown that when somebody is thinking that they might be rejected from the group, they're feeling as much pain as if they were really in pain, if something was really hurting them. It's the same parts of the brain. So when we, when we're thinking about, oh my gosh, if I go against the group, they might kick me out of the group. They might, they might publicly humiliate me. They, they, they. They might punish me. They might take it, you know, like that we have this physical pain from doing that.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:30:11]:

And so, you know, it, it may be that if we were really in our right man, it's like, so, okay. But when we're in the moment, it's like, oh, my gosh, you know, like, I can't, I can't. I can't go against the group. And so, and by, by not going against the group, we're reinforcing whatever it is that the group is saying to do. So then we move over in our mind, even if we're not 100% there yet, we're partial. The way that part of the way there to accepting it. We see this, you know, all up and down the line. We see this in family dynamics.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:30:43]:

We see this in companies. We see this in politics all the time, where, you know, we stake a view and. And if we really thought about it, it's like, you know, something, it's not that bad, or it's not all the way like this, but we don't. Because we're. We're part of that group that feels that way. Everybody else is feeling that way. We don't want to be. We don't want to go against it.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:31:09]:

So we. We go that way also, and then we move over in that direction.

Tyson Gaylord [00:31:13]:

What about the person in the group that's giving you about it or, or calling you names or, Or. Or really just kind of going after what. What is that person? What's happening in that person's mind or brain where they feel like they have to have this visceral reaction towards you saying you're dumb. That's not how it does. You know, whatever it is they're attacking you for. For questioning or challenging what the group is. Is saying.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:31:39]:

So in most of the cases, what they're feeling is that they're right. Okay. Okay. So they're in that binary state where something is right or something is wrong. You are going against the group norms. You have to be put in your place. Okay. So for the most part now, I also think that there's this.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:32:01]:

That there are just some people who are just so masterful that even though they know that, you know, they shouldn't be arguing with you, they know that that's the way to control you. And so you get an awful lot of. I would, you know, I guess an expression might be demagogues or autocrats. Okay. Who. It's like, you know something? The test of this person's loyalty is even though they know something is wrong, that they do it anyhow because it's coming from me. Wow. Okay.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:32:34]:

So those types of demagogues, they're always. They're. They're using it as a test. And when you do it, you become, you know, but you become much more aligned with them. And when you don't do it, they then crowd everybody else to say, look at this person. They're, you know, they're a piece of garbage. Okay, we want we. You know, we.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:32:53]:

And so they're, you know, anime, enemy fing. That's even a word. But enemy flying is one of the strongest ways to build cohesion in a group. You find something to hate, you find.

Tyson Gaylord [00:33:05]:

Something I'm an enemy.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:33:06]:

And you, and you get everybody. So this person has defied us. You know, we're all in this together. Look what this person did, you know, there. And, and you, and you bring the rest of the group together. So there are people who, who are so good at that, and they get into leadership positions that they're just using that in order to manipulate us.

Tyson Gaylord [00:33:28]:

Is there, is there something in their brain or something that, that their identity or something is being challenged and they have to kind of react and show, I don't know, their dominance or their, their smartness or education level?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:33:41]:

Yeah, I think, I think there is something of that. And they're all, you know, and again, and most of the people who are doing that are doing it because they're so sure that they're right and that you're wrong. And the way we're taught how to handle conflict, most of those ways really don't work over the long term. And so they're using, they're using the common ways of dealing with conflict, which is being aggressive or rewards or punishment being louder, which is really part of being aggressive. So, so, you know, most people, it's, it's not like their intentions are bad. It's just that they, that they know that they're right and that, and the standard ways of dealing with conflict is to just put down the other side. But I, I, I, I think we all should also be aware that there are certain people who understand how, that, how, how effective it is to do that. And so, you know, they know what they're saying is, is, is, is not in your best interest and, or whatever.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:34:47]:

But, but what they're trying to do is they're trying to consolidate their power. And they know that by doing that, they can consolidate their power with other people.

Tyson Gaylord [00:34:56]:

It reminds me of the 40 laws of power. The first law is never outshine the master. And I feel like some of that, some of that is there. Right? We also had the master. The master's like, hey, listen, buddy, I'm gonna put you back down. I know the game.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:35:07]:

Yep, yep, I'm the master. Okay, you don't, you, you don't do this.

Tyson Gaylord [00:35:11]:

Okay, Very interesting. One of your other frameworks, resilience. Can we, can we talk to resilience? Is that training? How do we talk? How do we think through this? How do we work through that?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:35:23]:

Okay, so, so the first part was resourcefulness. The resourcefulness is how do you access the most resourceful parts in your brain? Okay, now in resilience, we, we really start off with the way most of us approach situations, whether we approach problems or the way we approach opportunities. The, again, the human mind being binary. We look at situations of saying, you know, something, there's, there's going to be one right way of handling this. And very often it's like, you know what the right way is, okay, so there's one right way of handling this, which means that anybody who disagrees is wrong, right? Because if this is the way to handle it and you come up with something else, then. Then the other person is wrong. So that's, that's part of it. And then another part of it it is also means that we're going to do this and it's going to solve the problem.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:36:13]:

And the, and the issue that we get into is it's very rare that there's one right way, right? And it's, it's even rarer that the first thing that we do is really going to solve the problem. But if we're sure that this is the right way to do it and it's going to solve the problem, then when it doesn't, our reaction is to go into judgment or blame. It's like, oh, you know something, it wasn't my fault. It was just like, you know, everything conspired against me, or you got in my way, it's your fault, or, you know something, I'm just, I'm just an idiot. You know, I'll never amount to anything. It's my own fault. So we go into that, you know, blame my. Blame yourself, blame another person, blame the situation.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:36:53]:

And so we don't have, we don't have the resilience. The res, the resilience training is first of all to understand that that happens and then to say, well, okay, so, so how do you, how do you, how do you get above that? How do you, how do you respond in a way that allows you to keep on moving forward? Well, one way is to recognize that there are different types of situations. And clearly there are types of situations where there is a clear one right answer. Like, I'm thirsty right now. So here, here we go. Okay, that's clearly the right answer, right? But most things aren't that way. Sometimes you need more information. Sometimes you need analysis.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:37:39]:

Sometimes you need expertise. Sometimes you need expertise to figure out what to do. Sometimes you need expertise to do it, usually in situations like that, which are generally called complicated situations. So generally in complicated situations, there's more than one answer that could meet your needs. If you wanted to, to build a car or, you know, there's, there's a thousand ways to build cars. Okay? Now, you know, there's trade offs. Some cars will be less expensive, some cars will be faster, some cars will last longer. Some cars will use more gas, some cars will use, you know, so this, there may be trade offs, but in the end analysis, if your goal is to get a car to be able to go from one direction, one place to another place, any of those cars would meet that basic need.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:38:26]:

And if there's a bunch of people involved, it's, it's much less about finding like the only car that's going to meet your needs and it's more, it's, what's more important is that everybody buys into the fact that, hey, you know something, we could have bought any one of these four, five cars or we could have done any, any one of these six different things that we could have done. But let's just coalesce around one of them because we have to choose one so that everybody's on this, you know, on the same table. So we don't have like, you know, in the case of building a house, we don't have the carpenter who's following one set of plans and the electrician is following a different set of plans and the plumber doing something else. So, you know, to understand that there's complicated situations and in complicated situations you may need more information. And in all likelihood there's going to be more than one good way to, good way to act. And so you don't have to fight for one. You just have to coalesce everybody around something that's going to work. And then there's an awful lot of situations where nobody knows what's going to work.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:39:22]:

You know, like, can anybody, nobody has a solution to education. Like, there's no, you know, if people knew what was great education, we'd be doing it. Okay? But it's the fact that it's a complex problem that, you know, first of all, nobody knows what to do. And second of all, every time we do something that changes the whole system, that changes the whole way we measure things and then people react to that. And so you've got different problems every time you try to do something. And so with complex problems, which are different from complicated problems, the key is to be, is to try different things, knowing eventually something's going to emerge and you're going to try something, you're going to use the information you get back and that's, and then you're going to adjust and you're going to try something Else. Well, you talk about resilience, okay. If you're going into something and you're thinking, I'm going to do this and it's going to work and then it doesn't work.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:40:17]:

You know, you have to fight to get back in the game and that takes a lot of energy and that's really hard. You can't do that over the long term. But if you're going into the situation thinking, you know something, I don't really know what's going to work, nobody really knows what's going to work. But let's, let's just try these, these two or three different things and let's see what the information comes back and we'll figure out what to do next. That whole, you know, that you're, you're a lot more resilient and that whole issue of grit and persistence go, goes away because you don't have to fight to be persistent. It's like you're going into it knowing that, that there's, you know, that you're, you're just getting information so that you can choose the next thing and then, and then even from that you're going to get information and over time something's going to emerge and, and, and that's going to create the new status quo. So those are basically, you know, three way, three different types of situations. And then there's the fourth type of situation where something really is urgent.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:41:07]:

Something has to be done right away. Maybe you're in danger, like if your house is on fire, that's not the time to sit back and say, well, I should rewire the house so this doesn't happen again. Right, right. So, you know, with those emergency situations, that's where you have to do something immediately to get safe. You're not as concerned about a long term solution. You're just concerned about getting to a safe, you know, a safe situation. Like, you know, floods, fires, if you're in the middle of a fight with somebody, you know, your network goes, goes down in your company. You know, at that point, you know, you just, you have to get to the point where you're safe.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:41:45]:

And then afterwards you can consider the long term circumstances. And in those circumstances, you know, in those urgent, chaotic events, then in all likelihood you are in your limbic mind. And those same autocrats, those same demagogues as before, they know that if they can get you to think that something is urgent, they can put you into your limbic mind so that you lose the ability to think. And so one of the defenses is when Somebody is telling you this is a major problem, and you have to follow what I say. If we're going to get rid of the problem is to just stop and think, well, wait a minute, you know, is this such an urgent problem that only one thing is going to work and we have to follow this person and we have to do it now? And very often you're going to realize that, you know, the house isn't burning down, you know, you know, I can be a little bit more, you know, I can think about this a little bit more. I can. I can talk to people about it a little bit more. So, you know, there certainly are an awful lot of situations where there are crises and we do have to react quickly.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:42:56]:

But. But demagogues and autocrats tend to fake those situations so that we go into this fight or flight mode, going back to resilience. If you go into situations and you understand and you go into the situation and say, well, is this a situation where there really is one right answer. Is this a situation where, you know, I know that there's things that are absolutely going to work and I need some expertise or some analysis or information to come up with something that will work? And then that doesn't matter which of those things we choose, but, you know, we'll choose one of them and then we'll get everybody behind it. Or is this a situation where nobody knows what's going on? And so let's come up with a couple things that we can try, things that aren't going to hurt us, that we can get good information from so we can come up with our next step. Or is this really an urgent situation and somebody's just got to tell us all, you know, somebody's got to be the one to say, we all have to do this and we all have to get safe first. And so that's the, that's the first part of resilience. And then a second part of resilience is if you know that so many of the things that we do really are complex because people are complex, then what's a methodology that you can use so that you're always ready for more information? And in, in my courses and the book, and I actually go into this also in a little bit in the third book.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:44:16]:

The methodology that I use comes out of the military. It's developed by somebody named John Boyd, who was an Air Force pilot. Observe, orient, decide and act. OODA or ooda. And in OODA loops, basically your first step is to take in the information you're observing the Second step is to use what you already know and the information that's coming in and, and, and then, and figure out a few things that you could possibly do and what the likely results of those things are. And then the third step is deciding. That's when you're picking one or two things that you're going to try and then you're acting, but you're acting while you're observing. So you can, with, for the purpose of figuring out what you're going to orient the next, you know, what, what things you're going to come out with with, with next.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:45:10]:

And, and there's actually two different ways of thinking about the OODA loops. One is we're in the middle of, when we're in the middle of a situation, we have to be able to react fast. So in that orient step, the idea is to have as many things as possible that, you know, could possibly work and so preparing. So if it's an urgent situation, that's why we have fire drills. So we're prepared when the urgent situation comes up. When we go into the orient step is, okay, I know exactly what to do. This is a fire. I will, you know, I know where the exit is, I know how to get the people together, I know how to move out.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:45:48]:

So, so this, the fast OODA loop is using things that we've already come up with and then there's a much slower OODA loop which is, okay, we're, you know, we don't have a fire right now. But you know, I'm gonna make a figure up, you know, fight, you know, not 5%, but, you know, 1% of all houses have fire every year. And I know that figure's wrong, but, you know, so I know that there's a possibility that at some point my house will be, will go on fire. Let me come up with the emergency plan so that when that happens, everybody is ready. And so that slow OODA loop is preparing and practicing so that when the, when the situation occurs, we're much better able to, much better able to react.

Tyson Gaylord [00:46:27]:

How do you get, not get stuck in complacency? Say, listen, we have a fire drill every month and nothing ever happens. I'm not even playing this game anymore. How do you not get stuck in something like that where you're, you're, you're complacent?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:46:41]:

Yeah, that's a really good question. I think, I think it's human nature to get complacent.

Tyson Gaylord [00:46:48]:

Conservation of energy.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:46:49]:

Yeah, I think that, But I also think that, you know, you, you get Complacent until you hear of somebody else who didn't and suffered. And so, you know, I guess either you look or you or people look and say, you know, something. Look what happened to the Smiths two miles away. You know, you know, how. You know, how prepared are you? And so that kind of brings it back. But you're. You're right. It's.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:47:24]:

It's human nature to get complacent.

Tyson Gaylord [00:47:26]:

Absolutely. Reminds me of. I'm sure people listen, have heard the story a few times, but I'm. I'm big into stoicism, and one of the things Epictetus, one of the stoics, says is, you know, what are you afraid of? Sleeping on the floor, eating scan food, whatever. There's a whole list of things. So I took that to real, and I was like, hey, guys, you know, we're gonna do once a month is we're gonna just. I'm gonna make a pot of beans and rice and going to be just fine. I guarantee you we'll be all right.

Tyson Gaylord [00:47:54]:

And, you know, and I kind of played this little game with my kids, and then my eldest, she was like, this will never happen. There's no situation in my life, well, I'll ever have to do this and. And not. But I don't even know. Soon after, there's Covid, and the shelves are empty and. And it's like, hey, right, here we go. We're fine, right? Everybody's worried about this, that and another. But we've already practiced this.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:48:18]:

And.

Tyson Gaylord [00:48:18]:

Yeah, but there was the complacency of, like, oh, you're dumb, and why do we do this? But then it happens, and, you know, and it's interesting because it does, right? But, like, we're saying, right, you've got to go through the fire drills, and somehow we've gotta, I don't know, make it fun or something or make it interesting, and we stop the complacency. And there's probably a lot of situations in our lives where we do this, right? Especially things become habitual and just kind of go through the emotions. And he thought a treadmill and all these different things that kind of come up.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:48:49]:

So what you're bringing up in, you know, one of the ways of preparing is, like, if you're, you know, you're thinking of doing something and you want to be able to be resilient is okay. This is. This is what, you know, we're thinking living, you know, or we're thinking of doing this as a company. This is our course of action. This is our, our plan is what you know, called like the three stories, the three story technique. So say, okay, let's, let's, let's say you do this, tell me, you know, fast forward some period of time, six months, a year, five years, whatever the time frame is, and it was successful. Walk me through how that was, how that was successful and what happened and how you're feeling now that that that's successful. Okay, so that's story number one.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:49:39]:

Okay, now story number two. Let's say that it's whatever the time period is, let's say that it didn't work at all. Walk me through how implementing this ended up not working at all. Where you know, what happened in each step of the way and how is it six months from now? How does it feel? What are you doing now that it didn't work? And so that's, that's what, you know, kind of a pre, like a postmortem but a pre mortem. Okay, Right, right. What didn't work? Okay, so that's the second story. And then the third story is. Okay, let's just say that you implemented what's something that you absolutely could never expect happen.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:50:23]:

Something weird that just happens, you know, in your house, in your world and you know, something weird that happens that throws it all open. How do you, you know, what, what six months from now, a year from now, how did that affect this and what did you do now? Whatever that weird thing is that happens, that's almost guarantee you that particularly weird thing is not going to happen. But there's a good chance that something weird, something unexpected is going to happen. And just by preparing for something that was unexpected means that you're much better able to be prepared for anything else that happens unexpected. And by examining, you know, making the assumption that it didn't work, okay, you're going to be able to go through like either you're going to adjust your plans, you're going to make some minor tweaks, or you're going to say, you know something, maybe this plan really isn't the best because now that I'm looking at it, it probably wouldn't work. Or, and, and, and, and when you walk through how it did work the same, something similar is going to happen. Is you're going to say, well, we did this and this worked. Oh my gosh, I'm thinking about this, but the chances of that happening are really small.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:51:28]:

So maybe I have to go back and adjust something. So three Stories technique is, is really powerful to help people be more resilient as they're acting, you know, through their plans.

Tyson Gaylord [00:51:40]:

Yeah, I've heard of that. That does work really well. How do you. When you're going through this and you're. You're iterating, you're doing these things, you're trying to build resilience. How do you not get stuck in like a. Like a doom loop where you're like, you know, like all. You know, I'm doing these things.

Tyson Gaylord [00:51:57]:

It's like all this and this and that. I'm not. Hopefully, this is coming across. If you understand what I'm trying to get out there. How do you not get stuck in that negative thinking of, you know, you're trying to build resistance, but you're constantly in this negativity.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:52:13]:

That's it. So, you know, I have an answer. I'm not sure that it's a hunt. It's. It's 100% answer to your question. It is one of the ways. And that is, as you think of situations, you go through what, what people call the Walt Disney method. Are you familiar with it or do what.

Tyson Gaylord [00:52:35]:

No, I've never heard of it.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:52:36]:

So the Walt Disney method is. I think it's dreamer, realist, critic is the sequence. So, so you, you're going to go through stages. So the first stage is dreamer. It's like, what are all the things that I want to happen? And how, you know, how do I think they're going to happen? Okay, what, what should I do? And then the realist is, once you pick one or two of them, you say, how do I make this happen? And then the critic stage is, okay, so what could go wrong? And how would I. How would I overcome it? And it's. And it's an iterative process because then you go back to the dreamer stage. It's like, okay, well, given this, what do I really want to happen? What do I now think I want to happen? How, you know, I had these plans, now how do I adjust the plans to make sure it happens? And now what could go wrong? So by consciously going through that, you're.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:53:28]:

You're having your critic stage, but you all know that that's just a stage and you're going to revert to another stage.

Tyson Gaylord [00:53:36]:

Okay, thank you for that. I just was trying to think we're talking about the loop and stuff like that. I was like, oh, I can see somebody getting stuck in like a doom loop. Of like, this is this bad and we're never learning or we just suck. And, you know, so that's interesting. Yeah, kind of like we're kind of earlier, like a little maybe pre mortem, postmortem back casting something as well. Right. To try to work out these unknown unknowns maybe or whatever it is you're fear mongering yourself or something.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:54:00]:

Yeah. And, you know, going back to what do I want? What do I really want? Okay, what I really want to happen. And to understand that you're critiquing, your criticizing is not for the purpose of, of knocking something down, is for making something better. So how does this critique work to make something better? And then the other, the final thing is, is if this is a, you know, if this is a new type of situation, if it's a complex issue, you'll never get 100% certainty. And so it's the confidence of knowing that you're going to do something and you're going to get information back and that information is going to feed the next thing that you do. And so the whole purpose of that OODA loop is to get to action. And you don't want to spend so much time in that orient loop of putting things down because, you know, your purpose is to get into action, but on the same time, you don't want to skip that orient step because then you're not considering different alternatives, you're not considering what might go wrong.

Tyson Gaylord [00:55:05]:

Right. Yeah. I was, I was talking to somebody the other day a similar kind of thing where they're like, you know, we're saying I'm seductionist, all this stuff, and I gotta do it all myself. And I'm like, why? So I can't trust anybody else to do it. I was like, can you train up these people to do at least 80 of it and then you can come by and, and get the rest done and eventually you're going to train up a staff. And he was like, yeah, actually I could do that. I'm like, all right, let's move on here, buddy.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:55:27]:

No, and it just, just. I'm sorry. No, go ahead. Okay. When you said, you know, train these other people to do it, then that goes back. And I'm sure you, you said this also is your goal in being a manager, is your goal in running this company to always be doing it yourself? Right. So if your goal is not, then maybe letting people try things and letting them do it not quite as well as you do so that you can teach them. Maybe, maybe you're teaching somebody to fish instead of giving them fish.

Tyson Gaylord [00:55:54]:

Right, Exactly. If you're constantly handing these guys, they'll never learn. They can't fish as Good as me. You're just handing a fish. Well, there's no incentive to learn. I don't need to go fishing. I can go do something else. I, you just handed me the every day.

Tyson Gaylord [00:56:07]:

So speaking of that, I guess can we move on to collaboration?

Mitch Weisburgh [00:56:10]:

Sure, sure. So in collaboration, which is the third book, you know, at the beginning of the book we build somewhat of the foundation so we go into many, you know, the, some of the resourcefulness techniques and some of the resilience techniques so that you're prepared for conflict and collaboration. And so the, you know, the first part of the conflict and collaboration is to understand why so many of the techniques that we, that we naturally go to, to handle conflicts don't work. And very often they don't work because they put the other person into the feelings of being threatened or, or well, which, which then results into, into fight and flight. And they, they may comply but they may not, you know, but they may comply in the short term or while you're watching, but as soon you turn your back or as soon as you're not there, they'll go back and do what they wanted to do anyhow because they feel that they're being forced to do it. So the, you know, the data shows that trying to convince people with facts, trying to convince people with logic, trying to reward people, trying to punish people, trying to out argue people or just force them to do things. Some, you know, sometimes it has no effect, sometimes it has a short term effect. Like you know, if we're in this, the chaotic situation, you know, we, we have to get it, we have to get safe.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:57:47]:

But the long term effect of that, you know, it's, it's demotivating and it's not going to get people engaged to continue that, that, that type of work. So then kind of knowing that the next step in the book is to go through the five different ways of handling conflict. Okay. And so one of the ways of handling conflict is, you know, competitive is just, you know, you tell people what to do. We, you know, that's you know, like okay, you know, it's your bedtime, I'm the boss. Okay, okay. Or you know, like I, you know, I, I told you to do, I told you to do this report by, by 3:00 clock and it's 2:45 and you better have this on my desk in 15 minutes. You know, so that's a competitive, you're just telling me, you know, you're telling people what to do.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:58:37]:

The competitor is actually looking for the other person to be Accommodated. Use the accommodation technique. Which, and that's, that's can be a bit, you know, a valid technique is you're figuring out what the other person wants you to do and you, and you're doing it. So that's accommodating. Third is avoiding. And we all do that. Okay? Like this person is just going to tell me to do something I don't want to do anyhow, so I'm just going to kind of hide it from them or I'm, I'm not going to deal with this or you know, what's, there's no sense in arguing, so I'm just going to, I'm going to let them talk and then I'll do it my way anyhow. So avoiding.

Mitch Weisburgh [00:59:12]:

And then the two others are collaborating and compromising, which in English we very often think of our synonyms. But in conflict, you know, people who study conflict, they regard as two different things. When you're, you know, kind of, when you're settling, what you're doing is you're saying, well, look, you want these three, you want these five things? I want these five things. Why don't we do two of mine and two of yours? Okay, so nobody's 100 satisfied, but you know, we, the issue's behind us and we can move on. And then in collaborating, what we're trying to do is we're trying to expand the pie instead of splitting it. In collaborating, we're saying, look, I want these five things. You want these five things. What can we do that will meet, will meet both of our needs.

Mitch Weisburgh [01:00:02]:

That can be more work, but it also ends up being very often a longer, longer term solution. Not that any one of those five different ways of handling are wrong. So there are times where each one is advantageous and there's also, other than for collaboration for the other four, any one of the other four could be handled when we're in resourceful mode or when we're in fight or flight mode. So if we're competing for fight or flight mode, we're definitely causing resentment, okay? When we're accommodating, when fight or flight mode, we're just fleeing, okay? When we're, you know, when we're avoiding, we're also fleeting. When we're compromising, we're just saying, just, just settle it, you know, so. But on the other hand, when we're in resourceful mode, it's like, well, I, you know, you can still be assertive, you know, like you're, you may be the boss of a situation and there may Be, you know, three or four things that one could do. Somebody's got to make the decision. You don't have to do it in an aggressive fashion.

Mitch Weisburgh [01:01:04]:

You could just say, well, look, okay, we, we've heard all the information. We have to move forward, we have to make a decision. I know I would be upset also if somebody didn't pick my solution, but I'm just, I'm going to pick this one. I think this is a, this, this is a way to go these other ways they might have worked as well. This is the way we're going to go. Is everybody on board with this? And so you can do that from a, you know, phrasing it and from a position of being resourceful. So most of the, all of all five methods could be done from using resourceful brain, but four of them could also be used from using your limbic or your survival brain, which tends to stir up more, more negative emotions. So, so you learn the five different ways, you learn how to use them in both resourceful mode and in limbic mode.

Mitch Weisburgh [01:01:47]:

And then we go into what I mentioned before, interviewing. I just forgot the name of the term motivational interview.

Tyson Gaylord [01:01:58]:

Yes.

Mitch Weisburgh [01:01:59]:

Yeah. Which is a way of questioning and listening where you're getting the other person to really talk about, you know, if you're trying to sell them something or you're trying to get them to learn something, you're trying to get them to change their ways. They probably are somewhat ambivalent. If they really think about it about the way that they were originally thinking about doing it and it's getting them to talk about, well, you know, something, I was thinking about doing this, but now when I think about my main, my main goals, maybe it doesn't really align so much. And so if I think about my main goals, maybe there's three or four other ways of doing this. If, if they're picking up that you're doing this just to manipulate them that through really easily what you, you have to be, you know, you have to be empathetic, you have to be connecting with them. They have to feel that you're genuine, genuinely listening to them and interested in them. But the, you know, so motivational interviewing and then strengths based feedback.

Mitch Weisburgh [01:03:00]:

So instead of just giving people feedback based on this is what you should be doing. But using strengths based feedback as part of motivational interviewing and then nonviolent communications, which is a way of then phrasing what people should do in a way that makes them not feel that you're threatening them, makes them feel positive about it. And then once you have all those techniques, then the final chapter deals with group pressure and groupthink and how group pressure and groupthink and exacerbates all of our survival brain problems and how we can be, you know, we first have to learn how to get out of it ourselves and then things that we can do to work with others. And frankly, very often when you're getting into these group situations, one of the strategies is avoid. It's like, I'm just not going to bring this up because I know that, that this person, you know, I'm really not going to have an influence unless I spend a tremendous amount of time connecting with this person. I don't have that amount of time. So I'm going to put my efforts into the things where I can have the greatest, the greatest effect. And so that's.

Mitch Weisburgh [01:04:14]:

That basically is an outline of what's in the Conflict and Collaboration book.

Tyson Gaylord [01:04:17]:

Yeah, that's some good stuff for me. Some additional books I like on that is never split the difference from Chris Ross, the FBI negotiator. And then also he, in that book he recommends start with no. Also a great book.

Mitch Weisburgh [01:04:31]:

Yeah.

Tyson Gaylord [01:04:31]: